Today I am officially announcing that the title of my book in progress, formerly titled digital gothic: a spellbook for the new sorcerer, has been claimed by its rightful muses and will now be titled “Huginn & Muninn: a digital gothic.”

Today I am officially announcing that the title of my book in progress, formerly titled digital gothic: a spellbook for the new sorcerer, has been claimed by its rightful muses and will now be titled “Huginn & Muninn: a digital gothic.”

I also want to tell you a strange little story about how this book has come into being over the past two years. I will let you decide what to make of it, but I believe, personally, that the exhausting adventure/struggle that is writing a book is not merely a personal act. I think it’s a collusion, and I don’t think you necessarily get to choose who hijacks you and insists you tell their story.

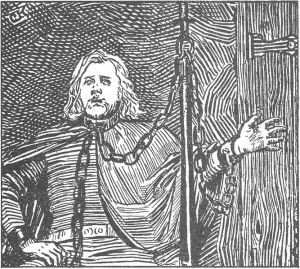

In the case of this book, my hijackers (or guides as I like to call them), are Huginn & Muninn. Never heard of them? Neither had I. In Norse mythology, they are a pair of ravens that accompany the god Odin. They fly out into the world(s) and bring back news of what they have seen. Their names translate to “thought” (Huginn) and “mind” or “memory” (Muninn). Odin’s relationship with these ravens is described in Scandinavian poetry from before and up to the 13th century including the Prose Edda, Poetic Edda, the Heimskringla saga, and in the work of a group of Icelandic poets called the skalds. I have not read any of these works, nor did I know about Odin being associated with ravens before they came to me in a dream. Though I have to admit I can relate in a very strong way to this image of a skald, composing poetry in chains after being captured by King Óláfr Haraldsson.

Not to be melodramatic about it, but being chained by the neck is an apt depiction of the internal landscape of most poets. This is why we cannot handle our liquor and why people tend to avoid our taste in books and movies.

Not to be melodramatic about it, but being chained by the neck is an apt depiction of the internal landscape of most poets. This is why we cannot handle our liquor and why people tend to avoid our taste in books and movies.

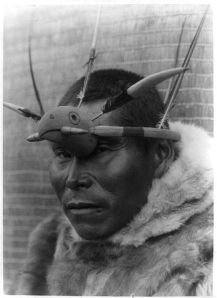

So yes, in case it slipped by you where I tried to hide it at the end of paragraph 3 above, I was approached by Huginn & Muninn in a dream. At the time, I knew nothing of who they were. You see, I have had a lifelong obsession with ravens. For my 12th birthday I had a raven tattooed across my left arm, shoulder, and back. (FYI: Every birthday has been my 12th birthday since I turned 12.) So ravens were not an unknown subject to me. I know the connotations Poe has given them, I know that they are scavengers, I know that their intelligence is on par with a dog’s (really a human’s but we don’t like to admit to these things), and that ravens live in family groups and can live for 70 years. In myth I was aware of raven as a trickster god, and in the Northwest native traditions is seen as a prometheus figure, having stolen the sun and brought it down to give warmth and light to human beings.

Then something happened. I was out walking at night. I was listening, for the very first time, to Virtual Boy’s Mass. I began to see things in my head, to connect internally to a time when I slipped in and out of such “seeing” quite easily- my early teens and twenties. A time when the plasticity of reality was still very much accessible to me. We are all magicians when we are young, but we don’t know it because we don’t know that reality actually solidifies as you get older. We don’t even have a way of understanding what the hell that means until it’s already happening. Before you think I am waxing sentimental, let me clarify: youth is not some precious, innocent state. I’m not forgetting the self-centeredness, short-sightedness, vanity, or naivety that are all rampant during that time, but I was remembering the effortless and absolute belief I had at a younger age that I could apparently influence the course of events by using mysterious or supernatural forces, which happens to be the first definition of magic. I think most teens and people in their early twenties think in that rational-magical way. It’s how new things happen.

Then something happened. I was out walking at night. I was listening, for the very first time, to Virtual Boy’s Mass. I began to see things in my head, to connect internally to a time when I slipped in and out of such “seeing” quite easily- my early teens and twenties. A time when the plasticity of reality was still very much accessible to me. We are all magicians when we are young, but we don’t know it because we don’t know that reality actually solidifies as you get older. We don’t even have a way of understanding what the hell that means until it’s already happening. Before you think I am waxing sentimental, let me clarify: youth is not some precious, innocent state. I’m not forgetting the self-centeredness, short-sightedness, vanity, or naivety that are all rampant during that time, but I was remembering the effortless and absolute belief I had at a younger age that I could apparently influence the course of events by using mysterious or supernatural forces, which happens to be the first definition of magic. I think most teens and people in their early twenties think in that rational-magical way. It’s how new things happen.

The thought that came to me, and the memory that immediately followed, was that I had once known how to travel into other worlds. Not the ill-advised and oft-regretted world of vodka shots. Not the blank room full of cats-in-hats behind the TV or inside the endless hypertrails of the internetz, but that portal that opens when you close your eyes and listen to certain kinds of music.

** I would like to note here, that the thought came to me, and then the memory followed. Odin’s ravens, remember, are called Huginn (thought) and Munnin (memory). Hindsight is interesting, isn’t it?

I credit my mother for this revelation about music as a door to other worlds. When I was about nine or ten years old, she once told me to lie on the floor and close my eyes and listen to Wagner’s Ride of the Valkries, and wait for pictures to come into my mind. “What do you see?” she asked me.

At first I saw the blood vessels in my eyelids, and then the phosphenes that swirl and houndstooth in flexing patterns behind your eyes when you are still “looking” but can’t see. And then I saw a bird… a white bird being chased through a storm by a black bird. I saw a battlefield. A war. All of it unfolding, happening as I watched. Not a thought, not a memory… just happening. Closing my eyes and entering that music was like stepping off the edge of the outside world into an equally vast inside world. This inside world, the one accessible through music, was unlike the world of dreams, or the world of deliberate imagining… it took me with it where it was going, not where I directed it. I did not know then that this simple act- to let go of the self and travel in this way- is the heart of the creative process. Disappearing the self is what all creative acts require, and ironically, it becomes more and more difficult to do this the more your “self” accumulates of the daily world.

We spend so much time arriving in and occupying our bodies. It’s all we think about. No wonder we get trapped. And the trick of the writer, unlike the dreamer, is to walk the slippery, crazy edge between this world and all the others– because the whole point, dear reader, is to bring things back….. for you.

So that night, walking through Golden Gate Park and listing to music in the dark, I began to see a vision in my head of a record spinning. And the record– this tight spiral line on a hard piece of stamped vinyl– was a code. If you have the right needle, that line becomes a song. Without it… you might go your whole life not knowing what that round piece of unremarkable plastic held– an entrance to another world. That night I went home and wrote: a magical circle, the first poem of the book. And then that night I had a dream that I was inside a giant Victorian house that suddenly ripped it’s foundations out of the ground, spread its eaves and took off into the sky. I was standing in the window, holding on for dear life and watching all the other houses in the city straining to get loose and take off. We entered a fogbank, and I couldn’t see anything but vague lights, and then I heard a very distinct sound next to me… feathers being blown in the wind. That’s when I saw the two ravens– one was surrounded by a cloud of black fire, and the other had wings entirely composed of hollow flutes that made chords and tones and music as it flew. They were both hanging in the air just outside the window, guiding the house out of the fog. When we emerged, we were over the Golden Gate Bridge, and heading for the open sea, only I wasn’t in the house anymore. I was a third raven. When I looked back, the house was still flying along, dodging in and out of the support cables of the bridge, along with some other houses. Through the windows, I could see people asleep in their beds, with no idea what was going on.

That dream gave me the seeds of the poems a candle, waking the dead, and gate crashing. It also made me want, more than anything, to get back in that dream. To be able to follow the ravens wherever it was they were going.

If you think I sound nuts, consider this: do you dream? How often are you able to remember your dreams? How often do you remember the dream just as you were waking up, but then lost it because you had another thought/started worrying about something you had to do/remembered you forgot to buy milk… and “poof” can’t remember the dream. Only that it was something strange, or important, or disturbing, or wonderful. You might grope for a few moments, trying to get it back, but the harder you try, the further it slips away. Sometimes you remember them, but when you speak them aloud or write them down… it is impossible to get across the sensation of significance in them. Sure, some dreams are just the regular old processing of anxiety and worry… or bits reassembled in a new and hilarious way. I had a dream, for example, that I was promoted to a new position in my job, they threw a big party for me, then when I got the piece of paper with my new job title on it, I discovered that I had been “promoted” to the job I already have. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out the underlying feelings that brought on that Dilbert-esque dream. I’m not talking about those sorts of dreams… I’m talking about the ones that come every once in awhile. The ones that are not like dreams at all, but travels.

If you think I sound nuts, consider this: do you dream? How often are you able to remember your dreams? How often do you remember the dream just as you were waking up, but then lost it because you had another thought/started worrying about something you had to do/remembered you forgot to buy milk… and “poof” can’t remember the dream. Only that it was something strange, or important, or disturbing, or wonderful. You might grope for a few moments, trying to get it back, but the harder you try, the further it slips away. Sometimes you remember them, but when you speak them aloud or write them down… it is impossible to get across the sensation of significance in them. Sure, some dreams are just the regular old processing of anxiety and worry… or bits reassembled in a new and hilarious way. I had a dream, for example, that I was promoted to a new position in my job, they threw a big party for me, then when I got the piece of paper with my new job title on it, I discovered that I had been “promoted” to the job I already have. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out the underlying feelings that brought on that Dilbert-esque dream. I’m not talking about those sorts of dreams… I’m talking about the ones that come every once in awhile. The ones that are not like dreams at all, but travels.

I’m here to tell you something: they are travels. You can go or not go… you can dismiss them and they will fade. Or you can pay attention, and dig deeper, and maybe go into territory you didn’t know existed. It’s just like the thread of song on the vinyl record. You would never think a piece of plastic could contain a song, just like you’d never think a dream could contain another world.

We are taught, at least in the culture I was raised in, that conscious control of our thoughts, actions, lives… deliberate decision-making with a very specific, intellectual part of the brain, is the highest form of self-control. The problem with this is that “doing” and “thinking” aren’t the same at all. I would even argue that you can’t really successfully do them at the same time. Doing is flow, and when you think “about” flow, you lose it. Creativity is very similar: it is the conscious act of relinquishing your self-consciousness. It is somewhere between dream and awake. The hard part is trusting it, and going with it. You can’t always dream yourself back into the dream… but once the ravens have appeared, you don’t really need to dream them anymore. That’s when you can sit down and enter the music, enter the creative headspace, and wait for them to appear…

I’m nothing if not curious, but I also rely heavily in my writing, on looking up things. If an idea appears in my work, I’m off to wikipedia, (Jung’s collective unconscious made manifest) to find out what people say about it. No subject is safe– physics, otters, politics, molecules– it’s all part of the continuum, and it’s all stuff to know and steal language from. So of course, I went looking into the ravens… and I found Huginn & Muninn, (or they found me). Check out what the page has to say about theories of their origin:

Theories

Scholars have linked Odin’s relation to Huginn and Muninn to shamanic practice. John Lindow relates Odin’s ability to send his “thought” (Huginn) and “mind” (Muninn) to the trance-state journey of shamans. Lindow says the Grímnismál stanza where Odin worries about the return of Huginn and Muninn “would be consistent with the danger that the shaman faces on the trance-state journey.”[20]

Rudolf Simek is critical of the approach, stating that “attempts have been made to interpret Odin’s ravens as a personification of the god’s intellectual powers, but this can only be assumed from the names Huginn and Muninn themselves which were unlikely to have been invented much before the 9th or 10th centuries” yet that the two ravens, as Odin’s companions, appear to derive from much earlier times.[11] Instead, Simek connects Huginn and Muninn with wider raven symbolism in the Germanic world, including the Raven Banner (described in English chronicles and Scandinavian sagas), a banner which was woven in a method that allowed it, when fluttering in the wind, to appear as if the raven depicted upon it was beating its wings.[11]

Anthony Winterbourne connects Huginn and Muninn to the Norse concepts of the fylgja—a concept with three characteristics; shape-shifting abilities, good fortune, and the guardian spirit—and the hamingja—the ghostly double of a person that may appear in the form of an animal. Winterbourne states that “The shaman’s journey through the different parts of the cosmos is symbolized by the hamingja concept of the shape-shifting soul, and gains another symbolic dimension for the Norse soul in the account of Oðin’s ravens, Huginn and Muninn.”[21] In response to Simek’s criticism of attempts to interpret the ravens “philosophically”, Winterbourne says that “such speculations […] simply strengthen the conceptual significance made plausible by other features of the mythology” and that the names Huginn and Muninn “demand more explanation than is usually provided.”[21]

So…. I thought… perhaps I am a little nuts. But I am clearly not the first poet to have been hijacked by the ravens of thought and memory… so who am I to break with tradition?

There is also something else: two years ago when I started writing this book, a google search of Huginn & Muninn revealed little more than a wikipedia page, and a few scattered pages on folklore. In the ensuing time, they have invaded the consciousness of artists all over the world. Try an image search of their names. Suddenly, I am not the only one dreaming about these ravens.

There is also something else: two years ago when I started writing this book, a google search of Huginn & Muninn revealed little more than a wikipedia page, and a few scattered pages on folklore. In the ensuing time, they have invaded the consciousness of artists all over the world. Try an image search of their names. Suddenly, I am not the only one dreaming about these ravens.

I can only hope I am up to the home stretch… of pushing through the daily grind to meet them, and to relay back this story that I’m stealing? borrowing? witnessing? in these other worlds. I know it will not let me go until I do… and frankly, I don’t want to let go of it either. It feels good to be able, finally, to fly in this way I always knew I could.

I think that this feeling of losing oneself in the moment, of not thinking about one’s self and of being in another space is important to experience…whether it be when you are totally immersed doing a dance, singing a song, listening to music, hiking somewhere, in yoga class, watching a movie or writing. Getting out of yourself is healing and gives your mind a chance to wander untethered by “reality”. It is often euphoric for me. It seems that your ravens are taking you to that special place and I look forward to traveling with them through your poetry.

Your avid fan

LikeLike

I recall those early twenties visions. ;)

LikeLike

What encourages me most about this thoughtful post is the courage it reveals about you, and, in turn, about all who dare to dream. Life is indeed beautiful and reality is most definitely absurd. Most of us appear oblivious to the fact that we are really sleepwalking through our lives and have very little awareness of who we are and our relationship to something greater. Lulled into believing we are “connected” to one another by an ominous digital network that prevents us from experiencing our true nature, we end up confusing thought and memory with tweet and overload. Write, paint, soar, compose, cry, listen, dance, feed, serve, suffer, heal, nourish, rejoice, dare, love, laugh, and, above all else, take none of it too seriously, particularly oneself..

LikeLike

Paul- thank you so much for these kind, thoughtful, and empathic words… and the encouragement is now mutual! :)

LikeLike

I remember the absolute windless silence of a desert canyon, the sky was radiant with afternoon sun. I was taken without warning by the feeling of childlike joy when two ravens flew silently overhead, muscle, sinew and feathers beating the air with the only audible sound. Magic arrives when you greet it. I know no person more open and capable of receiving it than you.

LikeLike

This means more to me than I can possibly say. Thank you.

LikeLike

I know you don’t like to *explain* your poetry, but I have to say it’s kinda neat getting this background story, though I’m also glad I heard the chapters you brought to our group without any preconceived notions first and was able to just revel in the mind-blowing kaleidoscope you conjured up with your raven wings.

On a more prosaic note, since you like to read different perspectives on your subjects, have you ever read Mind of the Raven? I couldn’t get into it — a little too obsessive for me — but some readers clearly loved it.

LikeLike

Thanks Sarah… it means a lot to me that you took the time to read and comment. I guess I don’t often “explain” my poetry because it forces an interpretation that might not resonate with the reader. I don’t want to interfere with that experience, unless the poetry isn’t succeeding, in which case I should keep working on it. But I do think that people rarely talk about the experience of creativity itself– how it spans the internal and external worlds.

LikeLike