Amor Paco

Paco spots the squat, rolling shadow crossing the deck and takes cover behind a coiled rope, watching as the captain disappears through the cabin door and slams his way down the companionway into his quarters.

It is a balmy day, sky clear, sea ruffled with a mild, steady breeze, but Paco shivers. The captain moves through the world, and around the ship, speaking with his fists. The moment he wakes in the morning he is angry, and as the day goes along his mood darkens until he begins to drink. The drinking turns his anger to sadness, and makes him want to talk. But he trusts no member of his crew, so he roars for Paco, who has little choice but to answer, hopping below to perch on the chair back at the captain’s table and listen to his sore thoughts. It has been this way since Paco was brought aboard, and life before that is now a place too distant to travel.

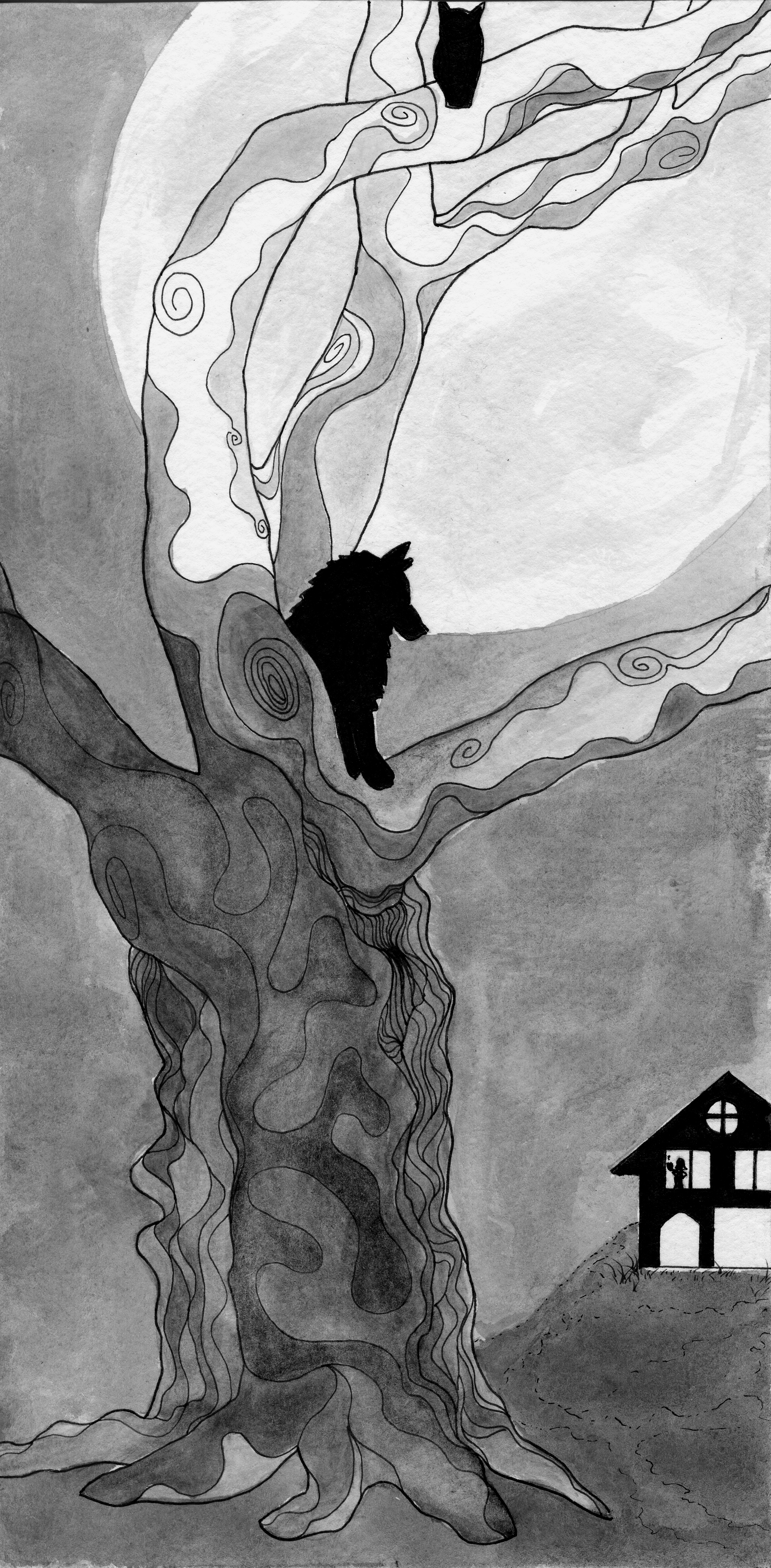

But it is early in the day yet, and hopefully, it will be hours before that forced confinement. Paco pokes one eye from behind the rope and rolls it skyward until it finds Abhi, sitting high above the deck on a yardarm. Paco launches into the air, soaring clear of the lines and sails, circling upward on a draft, landing neatly beside Abhi where he clings, hugging the mast and looking out to sea. Paco, says Abhi, reaching over to scratch at the spot where wing joins body. Together they watch the horizon tip gently, adjusting their bodies unconsciously with the wind and the yaw of the ship. P… A… C… O. You know what Paco means? says Abhi. Paco blinks slowly, pressing against the boy’s side, hoping for more of his absentminded scratching. Free, Abhi answers. It means free. He gives Paco a scratch behind the other wing. I bet the captain did not know this when he named you… or that you lay eggs! Abhi falls silent for a time, thinking. Paco presses closer to the boy, watching his eyes, where thoughts move like shadowy birds in a night sky.

Did you see the box they brought aboard at Cádiz?, Abhi asks. The cook says the captain won it in a card game our last night in port. I heard someone tried to come aboard in the night to take it back. There was shouting and a splash when they threw him overboard. Abhi shakes his head, leaning over to scan the deck below. The cook says the box contains a bad thing, a bad spirit. He whistles low, blowing out a long breath. Paco, Abhi says, you and I both know there are no bad spirits, no bad boxes- only bad people.

Abhi, Paco croaks. It is the only human word she has learned to say.

***

That night, Paco perches in her customary place on a chair back at the table in the captain’s quarters, but they are not alone: both mates and the bosun are also in attendance, each looking uncomfortable, each holding a cup of wine. The captain is drunk. On the table between them is a small box carved from a coffee-colored wood. There are four ornate letters worked into the lid, and an iron hasp that secures it. The captain keeps pulling it toward him in the midst of conversation, opening the lid just enough to glance inside, then closing it again, as if to check that whatever it contains is still there. Then he pours more wine, goes on talking, stroking the box gently with his fingertips. Paco watches the captain grow more drunk, his men more nervous, until finally, swearing, he sends them all away, slamming the door after the bosun as he scrambles up to the safety of the night.

The captain lurches to his feet, clutching the table’s edge to steady himself, his legs planted wide. He drags the box toward him, this time flipping the lid completely open and staring inside. Paco tilts her head, looking into the box first with one eye, then the other. There is nothing inside. She looks to the captain’s face, which is twisted in an expression Paco has never seen: pain, mixed with something soft… sadness, or hope? The box is reflected in the captain’s eyes, and in that reflection Paco can see that there is something inside the box. It is golden and glittering: a chain with a locket at the end. The captain shifts his gaze to Paco, glaring at her. He slams the box shut. What are you looking at, bird? Eh?

Paco grips the chair back tighter, prepares to hop to the far side of the table. It is not the first time Paco has danced with the drunk fists. But the captain is already forgetting this thought, now casting his eyes around the room, the box gripped in his hand. Can’t put it in the chest, he mumbles, the first place they’d look. His eyes come to rest on the liquor cabinet. He has made clear the punishment if anyone is caught stealing from it. On hands and knees, he stretches his arm into the darkness behind the bottles, tucking the box there, and passes out on the floor.

It is not until the small, cold hours of the night when door latch slowly lifts and the cook enters the room. He looks first toward the captain’s empty bed, then down to the floor where he lays beside the open cabinet. Paco, a shadow amid shadows, watches as the cook stoops down, snaking his arm into the back of the liquor cabinet, and pulls out the box. In the candlelight, Paco sees the double reflection in the cook’s eyes as he looks inside and scoops out a large, blood-colored jewel. The box is returned to its place. The cook creeps back to the door, exits without a sound.

***

The groaning begins near dawn. It’s not the captain, who still sleeps as if dead. It’s the ship. Her ribs creak. She rolls and wallows. The wind cries and then screams through the rigging. The first mate throws open the door, accompanied by a spray of rain. He crosses to the captain, shaking him, shouting in his ear, but he doesn’t wake. Paco escapes, hopping quickly up the stairs and into the storm, immediately blown back indoors by the force of the wind. She leaps to the galley window, watching the men scramble across the lurching deck, straining to find Abhi among them. The ship moans and wallows, her bow swinging to port and then starboard wildly.

Mother of God. The cook appears beside Paco, staring out the window. They hold on, watching as Abhi, thrusting himself from handhold to handhold, makes his way to the cabin door and swings himself into the galley.

Paco, Abhi says. Stay in. The wind will take you.

The cook grabs Abhi by the shoulder and shakes him. Forget the damned crow, he don’t understand you. Boy! What is happening? Why are we adrift?

The wheel’s gone. We can’t steer.

Gone? What do you mean… broken off? Did something strike us?

All three of them lurch as the ship swings hard to port. Paco flaps her wings to find balance, gripping with her feet. Abhi shakes his head, No, not broken… gone. The wheel is just… not there.

The cook swears, pushing Abhi out the door ahead of him. Paco watches them make their way through the wind toward the helm. The ship dips hard to starboard, and from overhead in the little berth where the cook slept, something drops and rolls, then ricochets off the galley wall and lands with a loud clang in a cast-iron cook pot. Paco hops to the rim of the pot and peers in: it’s the red gem. She seizes it in her beak. It is heavy, smooth and oval, like an egg. A great roar erupts from below decks followed by the bang of the captain’s quarters door. The first mate shoots up the companionway, the captain close behind, shouting, swine! Thief! They tumble out into the wind.

From the top of the companionway, Paco spots the box through the open door into the captain’s room. On its side on the floor, open and empty, it looks like a nest. Paco hops down the companionway toward it. Halfway down, the ship swings again and the door begins to close. Paco flies, the door clapping her hard into the room as it swings shut. By luck, she crashes onto the captain’s bed, still gripping the egg-like jewel. With two short hops, she reaches the box, drops the gem inside and flicks the lid closed with her beak. As if the storm were controlled by a switch, the wind stops. The ship ceases its sickening roll, and straightens as the rudder finds its bite and the ship resumes her steady course.

***

I’m telling you, Abhi says, rubbing his nose with his thumb, a storm can appear and disappear without reason, but a wheel cannot.

Paco clicks her beak and blinks her eyes. Her opinions of what is and is not reasonable are difficult to communicate. She had been perched on the chair back when the captain returned, steering the first mate by his hair, the cook following, trying to calm him. I’ll teach you to steal from me, the captain said, his grip on the mate’s hair pulling the skin on his forehead tight. The captain scooped the box from the floor, slamming it on the table. He forced the mate’s face close to it and flung the lid open. Paco was surprised to see it empty: where was the egg? She looked to the men’s faces. The cook stared; in the bottom of the box lay the red, egg-shaped jewel he knew he had taken: guilt, confusion, then fear flashed across his features. In the mate’s eyes, something else lay in the bottom of the box: a folded letter sealed with wax and the stamp of the queen. The captain’s face shifted from mean fury to a kind of despair: in his eyes, the object he thought stolen rested safely, its chain coiled in a neat spiral around an opened locket. On one side, the image of a woman, on the other, the image of a child. He let go of the mate and sat down hard in a chair. Get back to your duties, he had said quietly, turning to include Paco. Out!

Now, sitting in a patch of sun, peeling potatoes, Abhi and Paco keep a surreptitious watch on the wheel. The wind carries the conversation of the mates to them. I saw it myself: a letter in that box with the queen’s seal intact. The admiral must have received my report that he is not fit to command and he has received orders to relinquish, but he hasn’t opened them. The second mate, nodding, continues to inspect the helm, the wheel, all of its parts. Do you think he made up the story about the box, winning it in the card game, to put us all off? Does it have anything to do with someone taking the wheel and putting it back? The first mate takes his pipe out of his mouth and begins to pack it with tobacco. We’ll know when I get ahold of that letter.

A shadow falls across Abhi, making Paco jump. Always hanging out with that crow. The cook stands over them. His face, normally kind and a little mischievous, is haggard. How are the spuds coming? He follows their gazes to the men at the helm, then his eyes stray back toward the cabin. Abhi, I want you to stay clear of him as much as you can, he says. He’s ugly since we left Cadiz… since he brought that thing on board. There’s something in it, something not right about it.

How do you know? Abhi says, dropping a peeled potato into his bucket and picking up another. The cook scratches under his wool hat, frowning. Never mind that, he says. Hurry up with those potatoes.

Abhi starts on another potato with his small knife. She is not a crow, Abhi says, almost as if he is speaking to himself. She is kṛpate. Or Rāvēna. What? the cook says, his eyes on the mates, his thoughts elsewhere. Abhi looks startled, then worried. Nothing, he says, only… the bird, she is a raven. I remember these birds, where I came from. The cook has heard now, looks down at the boy. You remember where you came from? Abhi stares at his hands, the knife circling, the brown skin of the potato curling away into a long, dirty ribbon. Only a little, Abhi says, only sometimes.

Best not to look back, the cook says, tugging his hat lower and turning toward the galley.

***

Paco has never seen the captain in the mood he is in. He is not drinking or sleeping. He is not writing in the ship’s diary. He is not amongst the men, checking that everyone is doing their jobs. He is just sitting at the table, staring into the box, his hands holding the two sides of the locket. He is talking to the pictures there, or to Paco, or both. Paco isn’t sure.

Tell me how to make sense of it, he says. I lost you and now you’ve found your way back, but to what end?

Paco shifts on her perch, which catches the captain’s eye. Paco, he says. He lifts the necklace out of the box, holds it up carefully, as if he might break or bruise it. Do you see them? he asks. This is my wife, my son. He is about to say more when there is a knock at the door and Abhi enters carrying the captain’s supper.

Boy, the captain says. Set the plate down there and come here. Abhi tenses, his eyes wary, but he obeys. In a gentler voice, the captain asks, are you happy here? Abhi looks at the floor, watching Paco from the side of his eye. What is he to say? Is this question a trick? What has he done to make the man angry? He gives the only safe answer: Yes sir. There is a long silence as the captain stares into the boy’s face, waiting. Abhi, he says finally, do you remember anything of where you come from? Do you remember how you came aboard?

The captain has never called Abhi by name. It was always boy or you there! He did not know the captain even knew his name. In the years Abhi had been aboard the ship, no one ever asked him what he remembers, if he remembers… now he has been asked twice in a span of days… first by the cook and now the captain. How can he explain the voices, the images that rise in his mind when he sits high on the mast staring at the sea? How when he holds a cup, or a rope, or a stewpot, other words for these objects slide onto his tongue? How once he spelled out the letters carved onto one of the crew’s sea chest, and the man cuffed him across the face and told him never again to pretend he knew how to read. Abhi has learned to be quiet about what he knows, except to Paco.

I don’t remember… Abhi says, feeling he must say something, … anything before… before you brought me aboard. Only the ship.

Sometimes it is better not to remember a time before. The captain is not looking at Abhi now, but down at his hands. But you should know, it was not me that brought you aboard. Abhi looks up, all this time he had wondered, had guessed. Who had he been stolen from? Were his parents still waiting somewhere, wondering where he had gone, or believing he was dead?

Five years ago, in Bombay, there was an accident in the street. Your father, a schoolteacher, was killed. A member of my crew held himself responsible. Apparently, your mother was dead: you had no one else.

Abhi’s heart races. He has seen many ports, the slums and the hungry children on every dock looking for what they can earn or steal. The crew treat them like rats. Why had he been different? You took me in?

The captain looks up. No, he says. I did not know you were aboard until we were well out to sea. I don’t know how he thought he could keep you hidden. He knew the punishment for aiding a stowaway.

Who? Abhi asks.

The cook, the captain answers. He holds the boy’s gaze briefly, then turns back to the box on the table, reaching inside it.

Years before you, he says, I had a family. He holds the locket out toward Abhi, pointing at the tiny image on the left, my wife, then the right, my son. He was about your age. Abhi stares at the captain’s hands.

There you are! The cook has appeared in the doorway. The captain tucks the hand holding the locket behind his back. The cook looks harassed and sweaty. Get back to the galley. The pots won’t wash themselves. As Abhi turns to obey, Paco launches from the chair, landing on his shoulder. As they climb the companionway together, she looks back at the captain, still sitting at the table, watching them go.

***

I’m telling you, there was nothing there, Abhi says. He is scrubbing a large pot, his black hair plastered to his forehead from the steam. The cook leans against the stove, scratching beneath his wool cap.

But what did he say was in it? He told you about his wife and son… and he pointed at his hand while he said it?

Paco paces back and forth on the counter rail, her wings folded, clicking her beak. Abhi has said nothing about the rest of the story, about the accident, about being smuggled aboard. He had believed it all, until the moment the captain held up nothing in his hands and acted as if he held a treasure.

It was like he had something in his hand, Abhi says. Like he was holding something and pointing to pictures. He motions, pointing to one side of his palm, then the other. My wife, my son.

The cook stops scratching his head. His eyes widen and his mouth opens, then shuts. It can’t be.

What, what is it? Abhi says. Paco stops pacing, leans forward, blinking.

His wife and son… they took ill while we were at sea and died. He had a locket made. There was a picture in each side of it. But… The cook reaches up into the nook where he keeps his pipe and tobacco pouch and begins to pack it. A wet rag flies across the galley, smacking the cook in the side of the head and knocking his pipe away.

But what, Abhi says.

The cook looks angry, then scared. Lost, he says. That locket was lost years ago. The clasp broke and fell from his neck into the sea.

Abhi frowns. So he is losing his reason.

Or the locket has returned, the cook says. He puffs on his pipe as if the tobacco will help him make sense of what is happening. The box. That’s what he sees in the box.

There was nothing there, Abhi says. There is nothing in the box. Why do you believe there is something in that box?

The cook looks up, he doesn’t have to answer. He is not good at hiding things.

What did you see? Abhi asks.

The cook’s face and ears have gone a deep red, the red of a jewel that could have bought him a home, could have bought both he and the boy a future that did not include this dirty, stinking ship. But he does not say any of this. He is not a man who dreams aloud.

I hid it in my berth, the cook said. Then the wheel disappeared… and when I came back, the damn thing was back in the box. And the wheel… the wheel was returned.

Paco, unable to contain herself anymore, goes flapping and croaking around the room, then out the door and into the night sky. She flies for a long time, the wind riffling her feathers, sailing in and out of the rigging, wishing she did not have to understand the things she could not understand.

***

Paco and Abhi are in their favorite place, high up on a yardarm of the main mast. The ship has entered the zone of the equator where the breezes are fickle and the nights are so warm they sometimes sleep above decks in a hammock, though this means they are sometimes soaked by thunderstorms and driven in by squalls. But to fall asleep at night rocked by the movement of the ship, Abhi tracing with his finger a path from star to star, Paco nestled into the hollow beneath his arm, is worth the risk. Abhi has talked little about the story of the cook, the accident, his father’s death, but Paco sometimes wakes to see the shine of the boy’s eyes against the stars late at night, when he is awake alone, thinking.

It’s been two weeks since the night the captain showed Abhi the locket, and since then has moved about the ship as a different man. At first, the men had not known what to make of his, if not exactly sunny, steady and thoughtful demeanor. He looks them in the eye, listening to their reports. He moves about the ship offering terse praise for a job well done. He rousted the cook from his slovenly habits and ordered a full scrub-down of the galley as well as improvements in the men’s meals. After a week of this, the men had begun to believe it, shifting from an attitude of wary doubt to relief, and from that to a new morale. Feeling they can please the captain, they set out to do it. At night, he sits at table with them, listening to their stories. The ship feels, perhaps for the first time, like a brotherhood.

The cook has had much to say about it over his stewpot; he has not touched a drop to drink. I’ve been with him on one vessel or another for twenty years. I’ve never seen him like this- even before he lost his family, he was never a man to appreciate his crew. But then his face clouds over. Still, if it’s that box… it can only lead to trouble. To Abhi and Paco, the captain’s behavior is perhaps the most markedly changed. Used to being ignored unless wanted or not wanted, they are still surprised when he speaks to them now with a stern kindness. He asks to see what knots Abhi knows and set to teach him more, and how to use them. He feeds Paco biscuits and tries to get her to say her name.

There is one person on the ship who is not happy with this change. Paco and Abhi, from their windy vantage, watch the first mate leaning in an alcove where he keeps an eye on the activity on deck. Shoulders tense, he puffs like a dragon on his pipe. His hard eyes watch, watch. The more the captain has become involved with the men, the more the mate has grown quiet and detached, though never far off. He is waiting for something.

As if conjured, the captain appears at the cabin door. He strolls toward the foredeck. The first mate, watching from his alcove, waits until the line of sight between himself and the captain is broken. He checks that no one else is about, then crosses the deck and disappears into the cabin. Two, no more than three minutes pass, and he appears again, checking that no one has seen him. His hand is pressed to his breast pocket. He removes his cap and twists it in his hands, then makes his way aft where he finds the second mate. Their heads lean together as they talk. Paco cranes to listen, but they are too far up. The wind carries away all sounds but its own voice. Paco, Abhi says. He is looking to the horizon, one hand shading his eyes. Out where the blue line of the sea meets the lighter blue line of the sky, something glints.

As they watch, the glinting grows brighter, a thickening line of brightness creeping toward the ship, at first from the southwest, but then appearing on all sides, in all directions. It’s something on the water, Abhi says. Paco, without hesitation, dives into the air, riding a current clear of the ship. She chooses the direction of the ship’s progress, toward the lowering sun where the glinting is brightest. It doesn’t take her long to reach the edge. In tightening circles, she cruises lower and lower, finally thrusting her legs downward, wings tucked, and lands on the cold, whitish-blue surface. With her beak, she hammers a piece loose, picks it up, and carries it back to the ship.

Abhi is standing on the yardarm now. Hallooo! he calls to the men below, sweeping his arm in a circle describing the object on the sea that is closing around them. Paco lands. Abhi takes the object from her beak. Ice, Abhi says.

On deck, Abhi thrusts the melting piece of ice into the captain’s hand. Paco flew. She brought it back.

Pack ice, but how, at this latitude? The captain says. They break the sails, slowing the ship as much as they can, so as not to damage the hull against the approaching edge. By nightfall, they are stuck fast. The moon rises. The warm, equatorial air flows across the ship, stirring the hairs on the men’s arms and necks, while in every direction a frozen landscape reflects the light in weird ways. The men are silent. They all know what this means. They can do nothing until the ice releases them. They have all heard the stories of men caught in the ice for weeks, months, until their stores of food and water run out, and starving, some set out for land they will never find. Others, found months or years later, skeletons manning a ghost ship.

It can’t last, the captain said. It is too warm here. We’ve been thrown a freak, but it will blow over. The men want to take comfort from his words- strange things happen at sea- but this was the strangest any of them have seen. Fear settles onto their necks. So much of sailing is by feel, and this ice, coming from nowhere, from all directions as if sent to meet them, feels like more than an act of nature.

No, a voice says. It is not a freak. It is not even incompetence. The first mate steps forward. From his pocket, he draws a letter with a broken wax seal. He holds it up over his head for all the men to see. It flutters like a dying moth in the lantern light. Captain Pender, the mate says clearly, loudly. You have been remiss in your duties to this vessel. For months, you have spent your time drunk and abusing your men. You have let the running of the ship fall to those who kept her asail while you lay passed out in your cups. For two weeks, you have run this ship as a sober man, as an able man. But it is too late. It does not make up for years of neglect of duty. And this, he points to the horizon of ice off the port side of the ship, this shows that even as a sober man you cannot perform your duties as a captain.

No one spoke. All around them, the ice creaked and groaned and squealed, the sounds of mass forced against mass with no place to go.

I have a letter here, the first mate says, relieving Captain Pender of duty. It was delivered to him in Cadiz. He has kept it secret from us. I think, the mate says, his eyes cold, he knew he could not return to face such shame, he meant to sail us together, to our deaths. He meant to end his life and take us with him.

Paco, like a piece of the black sky, her eyes glinting stars, sails down and removes the letter from the mate’s hand. With two great flaps of her wings, she is through the cabin door and down the companionway, where she smashes into the closed door to the cabin’s quarters. Dazed, she rolls to her feet, eying the latch above her head. She could leap and turn it, but she would not be strong enough to pull it open. Feet thunder behind her. The cook grabs the rails on either side of the companionway, taking the stairs down three at a time. Move, he says, turning the handle and opening the door. Now go!

Together, they search the room for the box. Voices reach them from above decks: shouting, thumping. The cook finds the box stashed behind a chart at the corner of the captain’s desk. He sets it on the table and opens the lid. Paco, her claws clicking across the wood surface, drops the letter in, and flips it shut with her beak.

What are you doing?! It’s Abhi, standing just inside the open door. They are fighting! They are going to kill him! We have to do something! The cook snatches up the box and crosses the room, pushing Abhi out of the way. What are you doing? Abhi says. The cook heads up the companionway without answering.

At the top of the stairs, the cook comes face-to-face with the first mate, who is frog marching the captain, his face bloody. The crew follows loosely behind, arguing among themselves. Stop, the mate says, seeing the box in the cook’s hands. What are you doing? The cooks says nothing, but starts toward the starboard gunwale. The mate lets go of the captain’s arms, who crumples onto the deck. The cook, reaching the gunwale, draws back his arm to fling it outward, into the sea, but the mate has reached him, blocking the throw. They struggle. Paco, Abhi, and a few of the men reach them just as the mate overcomes the cook, wresting the box from his hands and kicking him to the deck. He stands, breathing hard, over the cook.

Look! Abhi shouts, pointing over the gunwale. The ice is gone. They are adrift on moving water. The mate opens the box, removes the letter, then flings the box high and hard, out into the dark water. He then reaches down and grabs the cook by the throat, hauling him to his feet. Traitor, the mate says. I’ll put you overboard. No! Abhi shouts, running toward the mate, grabbing hold of his sleeve, trying to make him let go. The wind gusts hard, dusting them with a spatter of rain, and the ship, drifting broadside to the wind, dips suddenly to starboard. The mate, trying to keep his balance, lets go of the cook, stumbles, and tips over the gunwale and into the sea, pulling Abhi with him.

Paco flaps as hard as she can against the wind. Two heads appear and disappear in the churning water below. She fights to get close without being driven into the water. Abhi. Abhi.

A head bobs up below, black hair plastered to the face. It is the mate, the letter still clutched in his hand. Images flash in Paco’s mind. She returned the egg: the wheel was found. She returned the letter: the ice disappeared. If she can get the letter again. Find the box. Put it back. All of this can be undone. She dives. She has it, in her beak, pulls it free, and is slapped out of the air. With his free arm, the mate catches Paco’s wing in his hand, and crushes the bones in his fist.

A wave knocks them apart. Paco, floating, watches the mate go under. The letter is still clutched in her beak. A dark, large shape lurches into view and then begins to grow smaller. The ship. Small figures wave from its deck. She rolls her eye, scanning the swells. Abhi. Abhi.

***

Paco hears waves, gentle waves breaking on shore. It has been years, how many years… since she has heard the sound. Her eyes open. A soft, wet wall rises against one side of her body, a yellow light blazes on the other. Not a wall, a beach. She is lying on the sand, the noon sun overhead. The letter is still tight in her beak. Her head, her wing, sing with pain, but she rolls onto her feet. There is something else down the beach; it is hard to make out. Her eyes blur. She limps, dragging the bad wing behind her.

It is the box. A few yards beyond it, a boy’s body stretches out on the sand. The face is turned toward her, the black hair dry, moving with the breeze. There is sand on Abhi’s face. It is hard to see clearly with this thing in her beak. The letter. The sea should have dissolved it. She should have let go of it, but she had not.

Paco drags herself to the box. She spits the letter into it. She shuts the lid, and keeps going until she reaches Abhi. She finds the spot she likes in the crook beneath Abhi’s arm, nestles there, goes to sleep.

***

Your wing is broken. Paco is lying on her back looking up into Abhi’s face, which is dusted on one side in a fine layer of sand. We can find something to splint it and see how it mends. Abhi carefully turns Paco over, and tucks her into the crook of his arm. As they walk up the beach the box comes into view. Abhi stops, leaning down to examine the lid. A…M…O…R. Amor, the boy says, reading the letters carved there. He flips the box lid open. Paco watches Abhi’s face, looking into his eyes. The box, reflected there, is empty. Abhi whistles low… You know what this word means? It means heart’s desire. It means love. He straightens and kicks the lid shut with his toe. Paco, you and I both know that no box can contain such a thing. Shading his eyes with one hand, Abhi tucks Paco closer, and heads up the beach, toward the trees.

Abhi, Paco croaks.